http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/features/adrian-ghenie-puts-fiends-in-the-frame-2362941.html

Peter Mallet

Peter Mallet

A five-metre long collage featuring a fox-hunt has some disconcerting aspects: a German bomber hovers at the top of the scene, and beneath, alongside the men in breeches riding and the rolling English countryside is a sinister-looking Siamese-twin dog running among the pack of Stubbsian hounds.

The collage, created in situ across the central wall at Haunch of Venison gallery in London, is the work of Adrian Ghenie, a 34-year-old Romanian artist with an interest in the legacy of Nazism, the English upper classes, and the misuse of science.

Ben Tufnell, director of exhibitions at Haunch of Venison, says his 12 new works bring together historical figures such as the evolutionary scientist, Charles Darwin, and Josef Mengele, the German physician at Auschwitz, to connect ideas of aristocratic “breeding” with Nazi eugenics.

“He was a child when Ceausescu was in power and a teenager when the transition happened,” explains Tufnell. “He grew up under that aura ofpolitical darkness, and he could see its lingering traces around central Europe.”

Having lived in Berlin before moving to London, he became interested in the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute, which was set up in the early 20th century. Despite its high principled aims, it became one of the places where the eugenics experiments were conducted. Ghenie says: “I am interested inthe presence of evil, or more precisely, how the possibility for evil is found in every endeavour, even in those scientific projects which set out to benefit mankind.”

This group of paintings explore the theme of scientific research that is turned on its head, adds Tufnell. “Charles Darwin’s ideas, for example, were co-opted by the Nazis, such as the concepts of natural selection and the survival of the fittest.”

Ceausescu is the subject of the portrait Study for “Boogeyman”, which shows the dictator in a state of physical disintegration. Ghenie created this work when it emerged that Ceausescu’s body, along with that of his wife’s remains, had been disinterred from their graves last year, after speculation that they had never been killed.

Ghenie has created tableaux of evil that range across 20th-century dictatorships in the past: portraits of Hitler’s key henchmen, the Nazi leader’s Bavarian residence (the Berghof), Stalin’s tomb and Lenin’s dead body.

Adrian Ghenie, Haunch of Venison, London W1 (www.haunchofvenison.com) to 8 October

Adrian Ghenie, Dada is Dead, 2009, Oil on canvas, 220 x 200 cm

First Dada fair

MAN RAY

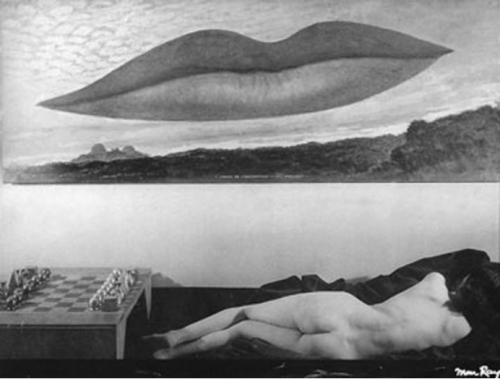

l'Heure de l'Observatoire: les Amoureux (Observatory Time: The Lovers) (1936)

Artwork description & Analysis: One of Man Ray’s most memorable paintings, Observatory Time, is featured in this black-and-white photograph, along with a nude. It includes a depiction of the lips of his departed lover, Lee Miller, floating in the sky above the Paris Observatory. In the photograph, the nude is lying on her side on a sofa underneath the painting, with a chessboard at her feet. Observatory Time hints at what the woman might be dreaming: a nightmare or an erotic fantasy. The lips in the picture were an inspiration for the logo of The Rocky Horror Picture Show, and many other pop culture iconic images. The chessboard appears in many of the artist’s works - Duchamp, Picabia and Man Ray all loved playing chess. And Man Ray considered a grid of squares, “the basis for all art… it helps you to understand the structure, to master a sense of order.” He also made chess set designs and photographs of chessboards, pieces and players.

DADA

the first words of a child, and these suggestions of childishness andabsurdity appealed to the group, who were keen to put a distance between themselves and the sobriety of conventional society. They also appreciated that the word might mean the same (or nothing) in all languages - as the group was avowedly internationalist.

The aim of Dada art and activities was both to help to stop the war and to vent frustration with the nationalist and bourgeois conventions that had led to it. Their anti-authoritarian stance made for a protean movement as they opposed any form of group leadership or guiding ideology.

“DADA, as for it, it smells of nothing, it is nothing, nothing, nothing.”

Francis Picabia

Synopsis

Dada was an artistic and literary movement that began in Zürich, Switzerland. It arose as a reaction to World War I and the nationalism that many thought had led to the war. Influenced by other avant-garde movements - Cubism, Futurism, Constructivism, and Expressionism - its output was wildly diverse, ranging from performance art to poetry, photography, sculpture, painting, and collage. Dada’s aesthetic, marked by its mockery of materialistic and nationalistic attitudes, proved a powerful influence on artists in many cities, including Berlin, Hanover, Paris, New York, and Cologne, all of which generated their own groups. The movement dissipated with the establishment of Surrealism, but the ideas it gave rise to have become the cornerstones of various catogeries of modern and contemporary art.

Key Ideas

Dada was the first conceptual art movement where the focus of the artists was not on crafting aesthetically pleasing objects but on making works that often upended bourgeois sensibilities and that generated difficult questions about society, the role of the artist, and the purpose of art.

So intent were members of Dada on opposing all norms of bourgeois culture that the group was barely in favor of itself: “Dada is anti-Dada,” they often cried. The group’s founding in the Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich was appropriate: the Cabaret was named after the eighteenth century French satirist, Voltaire, whose novella Candide mocked the idiocies of his society. As Hugo Ball, one of the founders of both the Cabaret and Dada wrote, “This is our Candide against the times.”

Artists like Hans Arp were intent on incorporating chance into the creation of works of art. This went against all norms of traditional art production whereby a work was meticulously planned and completed. The introduction of chance was a way for Dadaists to challenge artistic norms and to question the role of the artist in the artistic process.

Dada artists are known for their use of readymade objects - everyday objects that could be bought and presented as art with little manipulation by the artist. The use of the readymade forced questions about artistic creativity and the very definition of art and its purpose in society.

Duchamp was the first artist to use a readymade and his choice of a urinal was guaranteed to challenge and offend even his fellow artists. There is little manipulation of the urinal by the artist other than to turn it upside-down and to sign it with a fictitious name. By removing the urinal from its everyday environment and placing it in an art context, Duchamp was questioning basic definitions of art as well as the role of the artist in creating it. With the title, Fountain, Duchamp made a tongue in cheek reference to both the purpose of the urinal as well to famous fountains designed by Renaissance and Baroque artists. In its path-breaking boldness the work has become iconic of the irreverence of the Dada movement towards both traditional artistic values and production techniques. Its influence on later twentieth century artists such as Jeff Koons, Robert Rauschenberg, Damien Hirst, and others is incalculable.

Ici, C'est Stieglitz (Here, This is Stieglitz) (1915) Reciting the Sound Poem Untitled (Squares Arranged according to the Laws of Chance) (1917) Fountain (1917) LHOOQ (1919) Cut with a Kitchen Knife Dada through the Last Weimar Beer Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany (1919) The Spirit of our Time (1920) Chinese Nightingale (1920) Rayograph (1922) Merzpicture 46A. The Skittle Picture (1921)

Beginnings

Switzerland was neutral during WWI with limited censorship and it was in Zürich that Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings founded the Cabaret Voltaire on February 5, 1916 in the backroom of a tavern on Spiegelgasse in a seedy section of the city. In order to attract other artists and intellectuals, Ball put out a press release that read, “Cabaret Voltaire. Under this name a group of young artists and writers has formed with the object of becoming a center for artistic entertainment. In principle, the Cabaret will be run by artists, guests artists will come and give musical performances and readings at the daily meetings. Young artists of Zürich, whatever their tendencies, are invited to come along with suggestions and contributions of all kinds.” Those who were present from the beginning in addition to Ball and Hennings were Hans Arp, Tristan Tzara, Marcel Janco, and Richard Huelsenbeck.

In July of that year, the first Dada evening was held at which Ball read the first manifesto. There is little agreement on how the word Dada was invented, but one of the most common origin stories is that Richard Huelsenbeck found the name by plunging a knife at random into a dictionary. The term “dada” is a colloquial French term for a hobbyhorse, yet it also echoes the first words of a child, and these suggestions of childishness and absurdity appealed to the group, who were keen to put a distance between themselves and the sobriety of conventional society. They also appreciated that the word might mean the same (or nothing) in all languages - as the group was avowedly internationalist.

The aim of Dada art and activities was both to help to stop the war and to vent frustration with the nationalist and bourgeois conventions that had led to it. Their anti-authoritarian stance made for a protean movement as they opposed any form of group leadership or guiding ideology.

The Spread of Dada

Parties at Cabaret Voltaire

The artists in Zürich published a Dada magazine and held art exhibits that helped spread their anti-war, anti-art message. In 1917, after Ball left for Bern to pursue journalism, Tzara founded Galerie Dada on Bahnhofstrasse where further Dada evenings were held along with art exhibits. Tzara became the leader of the movement and began an unrelenting campaign to spread Dada ideas, showering French and Italian writers and artists with letters. The group published an art and literature review entitled Dada starting in July 1917 with five editions from Zürich and two final ones from Paris. Their art was focused on performance and printed matter.

Once the war ended in 1918, many of the artists returned to their home countries, helping to further spread the movement. The end of Dada in Zürich followed the Dada 4-5 event in April 1919 that by design turned into a riot, something that Tzara thought furthered the aims of Dada by undermining conventional art practices through audience involvement in art production. The riot, which began as a Dada event, was one of the most significant. It attracted over 1000 people and began with a conservative speech about the value of abstract art that was meant to anger the crowd. This was followed by discordant music and then several readings that encouraged crowd participation until the crowd lost control and began to destroy several of the props. Tzara described it thus: “the tumult is unchained hurricane frenzy siren whistles bombardment song the battle starts out sharply, half the audience applaud the protestors hold the hall … chairs pulled out projectiles crash bang expected effect atrocious and instinctive … Dada has succeeded in establishing the circuit of absolute unconsciousness in the audience which forgot the frontiers of education of prejudices, experienced the commotion of the New. Final victory of Dada.” For Tzara the key to the success of a riot was audience involvement so that attendees were not just onlookers of art, but became involved in its production. This was a total negation of traditional art.

Soon after this, Tzara traveled to Paris, where he met André Breton and began formulating the theories that Breton would eventually call Surrealism. Dadaists did not self-consciously declare micro-regional movements; the spread of Dada throughout various European cities and into New York can be attributed to a few key artists, and each city in turn influenced the aesthetics of their respective Dada groups.

Germany

Closer to a war zone, the Berlin Dadaists came out publicly against the Weimar Republic and their art was more political: satirical paintings and collages that featured wartime imagery, government figures, and political cartoon clippings recontextualized into biting commentaries.

New York

The 1918 Dada Manifesto had declared: “Every page must explode, whether through seriousness, profundity, turbulence, nausea, the new, the eternal, annihilating nonsense, enthusiasm for principles, or the way it is printed. Art must be unaesthetic in the extreme, useless, and impossible to justify.”

Paris

After hearing of the Dada movement in Zürich, a number of Parisian artists including Andre Breton, Louis Aragon, Paul Eluard, and others become interested. In 1919 Tzara left Zürich for Paris and Arp arrived there from Cologne the next year; a “Dada festival” took place in May 1920 after many of the originators of the movement had converged there. There were several demonstrations, exhibitions, and performances organized along with manifestos and journals published, including Dada and Le Cannibale.

Picabia and Breton withdrew from the movement in 1921 and Picabiapublished a special issue of 391 in which he claimed that Paris Dada had become the thing it originally fought against: a mediocre established movement. He wrote: “The Dada spirit really only existed between 1913 and 1918 … In wishing to prolong it, Dada became closed … Dada, you see, was not serious… and if certain people take it seriously now, it’s because it is dead! … One must be a nomad, pass through ideas like one passes through countries and cities.” Paris Dada published a counter-attack under the direction of Tzara. Two final Dada stage performances are held in Paris in 1923 before the group collapsed into internal infighting and ceded to Surrealism.

Marcel Duchamp provided a crucial creative link between the Zürich Dadaists and Parisian proto-Surrealists, like Breton. The Swiss group considered Marcel Duchamp’s readymades to be Dada artworks, and they appreciated Duchamp’s humor and refusal to define art.

Irreverence不敬

Irreverence was a crucial component of Dada art, whether it was a lack of respect for bourgeois convention, government authorities, conventional production methods, or the artistic canon. Each group varied slightly in their focus, with the Berlin group being the most anti-government and the New York group being the most anti-art. Of all the groups, the Hannover group was likely the most conservative.

Wit and Humor 机智和幽默

Tied closely to Dada irreverence was their interest in humor, typically in the form of irony. In fact, the embrace拥抱 of the readymade is key to Dada’s use of irony as it shows an awareness that nothing has intrinsic value内在价值. Irony also gave the artists flexibility and expressed their embrace拥抱 of the craziness of the world thus preventing them from taking their work too seriously or from getting caught up in excessive enthusiasm陷入过度的热情 or dreams of utopia乌托邦. Their humor is an unequivocal YES to everything as art.

Further Developments

As detailed above, after the disbanding of the various Dada groups, many of the artists joined other art movements - in particular Surrealism. In fact, Dada’s tradition of irrationality and chance led directly to the Surrealist love for fantasy and expression of the imaginary. Several artists were members of both groups, including Picabia, Arp, and Ernst since their works acted as a catalyst in ushering in an art based on a relaxation of conscious control over art production. Though Duchamp was not a Surrealist, he helped to curate exhibitions in New York that showcased both Dada and Surrealist works.

Dada, the first conceptual art movement, is now considered a watershed moment in twentieth-century art. Postmodernism as we know it would not exist without Dada. Almost every underlying postmodern theory in visual and written art as well as in music and drama was invented or at least utilized by Dada artists: art as performance, the overlapping of art with everyday life, the use of popular culture, audience participation, the interest in non-Western forms of art, the embrace of the absurd, and the use of chance.

Most of the artistic movements since Dada can trace their influence to that group. Other than the obvious examples of Surrealism, Neo-Dada, and Conceptual art, these would include Pop Art, Fluxus, the Situationist International, Performance art, Feminist art, and Minimalism. Dada also had a profound influence on graphic design and the field of advertising with their use of collage.

Hannah Höch

German Photomontage artist

Movement: Dada

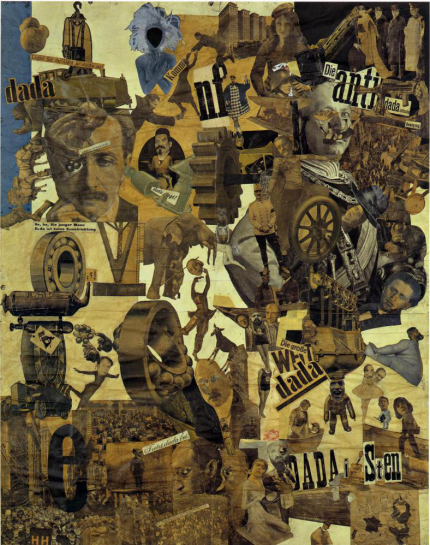

Cut With the Kitchen Knife Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany (1919-20)

Artwork description & Analysis: Though one of Höch’s earliest works, this ambitious collage is unusual within her canon for being particularly large; it measures 35 x 57 inches. Here she uses cuttings from newspapers and magazines to create one cohesive image out of a myriad of disparate parts. This technique of taking words and images from the established press to make new and subversive statements was highly innovative.

The piece was exhibited in the First International Dada Fair, which took place in Berlin in 1920, and it was reportedly one of the most popular pieces in the show. In the top right corner Höch has pasted together images of “anti-Dada:” figures of the Weimar government and representatives of the old empire. Elsewhere in the collage, the proponents of Dada including photographs of Raoul Hausmann are ranged in opposition to these establishment figures.

The effect is initially one of visual confusion, and yet a kind of nonsense-narrative begins to develop with sustained attention. One figure is transformed into something else by the addition of a de-contextualised newspaper clipping, such as the Kaiser’s iconic moustache replaced by a pair of upside-down wrestlers. The work encapsulates the eclecticism and eccentricities of Dadaism, but also makes a pointed political statement against the staid establishment; it is a carefully-crafted homage to anarchistic opposition.

Photomontage

Hannah Höch

GERMAN ARTIST

WRITTEN BY: Naomi Blumberg

Those credited with employing and elevating collage to a fine art, namely Picasso and Georges Braque, had incorporated some photo elements, butHöch and the Dadaists were the first to embrace and develop the photograph as the dominant medium of the montage. Höch and Hausmann cut, overlapped, and juxtaposed (usually) photographic fragments in disorienting but meaningful ways to reflect the confusion and chaos of the postwar era. The Dadaists rejected the modern moral order, the violence of war, and the political constructs that had brought about the war. Their goal was to subvert颠覆 all convention, including conventional modes of art making such as painting and sculpture. Their use of photomontage, which relied on mass-produced materials and required no academic art training, was a deliberate repudiation故意颠覆 of the prevailing German Expressionist aesthetic and was intended as a type of anti-art. Ironically, the movement was quickly and enthusiastically absorbed into the art world and found appreciation among connoisseurs of fine art in the 1920s.

Adrian Ghenie

The Romanian painter Adrian Ghenie was just 12 years old in 1989, when the military trial of the ousted Communist president Nicolae Ceauescu and his wife, Elena, took place. Hanging on Ghenie’s classroom wall, as in many schools and institutions around the country, was a portrait of the president looking suitably youthful, kindly, and forthright. The televised images of the trial came as a shock to him. “We didn’t really believe it was Ceauçescu because he looked so old,” says Ghenie. “Looking at their faces during the trial, you could see the human dimension of these people.” On a trip to the National Museum in Bucharest, site of a solo exhibition of his work,

the artist takes the opportunity to show his guests the museum storeroom, which is filled with thousands of commissioned, largely propagandistic portraits of Ceauçescu. In contrast to these, Ghenie’s painting Nicolae, 2010, shows a man who seems not to really know what’s going on; his face, only loosely and lightly defined, in flesh tones dirtied by gray, reveals a suggestion of eyebrows raised in mild confusion and small pale eyes evincing bemused resignation. A picture of Elena, also as she appeared during the trial, portrays her as more doleful and forlorn, rendered in Ghenie’s trademark palette of sepia, brown, and black. According to some accounts, Nicolae’s last gesture before the pair’s hasty execution at a military base was to sing The Internationale; his wife simply said, “Fuck you all.” Ghenie smiles. “At least she realized it was over.”

These portraits of the living, if doomed, couple are something of a departure for Ghenie, who has previously painted totalitarian leaders as lifeless bodies, including, in Found, 2007, Lenin lying in state. “The image of the dead Ceauçescu is an image that I will never use,” he explains. “It’s too vulgar somehow. There’s nothing I can do with it.” The scene of their execution, however, fueled his imagination. Ghenie saw a documentary made by an American news team that discovered and filmed the abandoned military base where the couple was shot; it was still intact though clearly decaying, with plants growing inside and stray dogs wandering freely. This scene inspired Ghenie’s The Trial, 2010, portraying how he envisions the couple’s day in court. The painting shows a shabby interior that, with its shoddy floorboards, rust-red wooden paneling, and curtain seemingly the worse for wear, looks like a run-down social club. The accused sit huddled in the shadows of the makeshift courtroom, wedged into a dark corner by two cheap trestle tables. Facing them are a simple wooden chair and a strangely incongruous floral-upholstered armchair, both empty, positioned as if awaiting an interrogator or torturer. The couple, the only figures in the scene, seem more like squatters than dignitaries. Elena wears what appears to be a tiger-skin coat, symbolizing the extravagant lifestyle she once enjoyed. According to Ghenie, she would often appear in public wearing rare furs, rumored to be from zoo animals she had had killed but more likely to have come from the African dictators with whom Nicolae was friends.

Elena’s coat ties The Trial to Berlin Zoo, 2009, both of which were first presented at Mihai Nicodim Gallery, in Los Angeles, this year. A beautiful male tiger commands the foreground of the second work, which depicts a zoo whose ruinous state is reflected in Ghenie’s brush marks, which slide from figuration to abstraction in unreadable passages of paint. The tiger’s body twists toward a lioness that is lying on the ground and could be either asleep or dead, although the striations of blood-red paint running down the picture plane and over her body make the latter more likely. On the left side of the painting another lioness, with meat in her mouth, looks on from a cage that is only partially barred, implying that she is free but has not yet ventured out. A monkey can be discerned amid blurry marks, scraped pigment, and exposed canvas. The scene is claustrophobic, as if it were a grotty basement rather than an open-air zoo. This impression is enhanced by a thick, heavy-looking chunk of rusty metal or masonry hanging in the air above like a roof blown apart by an aerial assault. Indeed, a ghostly MiG fighter plane emerges from the forbidding gray wall that recedes into the shadows behind the figures. Ghenie is clearly inviting the viewer to make a connection with the well-documented bombing of Berlin’s Tiergarten during World War II. In a related image, Berlin Zoo II, 2009, an almost monochrome baby rhinoceros can be seen peering through a hole in a wall. “Everyone thought that all the animals in the zoo had died,” explains Ghenie, “so when news emerged that a baby rhino was still alive, people started a campaign to feed it, even though there was a major food shortage at the time.”

This series is part of Ghenie’s long-standing exploration of animals out of context, but it was also inspired by the filmmaker Emir Kusturica’s 1995 black comedy Underground. The film follows two Yugoslav men from World War II through their country’s violent breakup in the 1990s. In an early sequence, Belgrade is bombed by the Nazis, after which all kinds of animals are seen roaming the capital’s streets, indicating that the zoo has been hit. “As an image, it’s so powerful,” says Ghenie. “A central European set with exotic animals.” (用)This scene is key to interpreting the connection between the artist’s depiction of the Ceauçescu trial and his Berlin Zoo paintings: Exotic animals in the streets symbolize the strangeness following dramatic political change, whether through revolution or war, for those experiencing the breakdown of their familiar social structures.

“It was very weird growing up during the revolution years,” Ghenie says. “Nobody really understood what was going on.” The power vacuum left by Ceauçescu’s death led to a period he describes as regrettable and yet liberating. “It’s always like that when a system collapses and the new leadership is under construction: They let you get away with whatever you want. In 1993 you could stand up in public and say whatever you liked. Nobody was arrested, because the authorities would do nothing that made them seem too much like the old regime.” Many people left Romania at this time, hoping for a better standard of living. This emigration, along with the period’s anarchy, was one of the themes underpinning Ghenie’s concurrent 2008 exhibitions at Nolan Judin Berlin and Plan B Berlin. “A lot of people survived doing bad things,” he says. “They weren’t all bad people. You would be amazed by the transformation if you put a nice guy in the wrong context.”

Ghenie’s paintings often tend toward melancholy and regret, abjection and anomie, and his Ceauçescu and Berlin Zoo works are no exception. Although not devoid of hope (let’s not forget that baby rhino), they are saturated with the loneliness, darkness, disillusionment, and repression that characterizes his oeuvre. Underneath the exoticism and surrealism, he offers a bleak vision of the Eastern bloc, a disturbing psychological account of the history of communism in Europe. The wall of the zoo, clearly a metaphor for the Berlin Wall, is linked as well to the wall of the courtroom where the Romanian dictator was tried. The zoo becomes a symbol for both East Berlin after 1945 and for Romania under Ceauçescu.

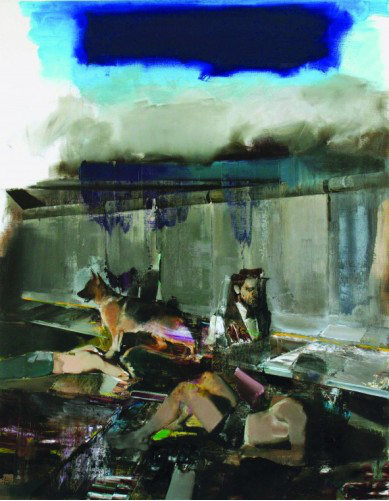

The theme of the Berlin Wall also runs through a series that Ghenie started for his solo show at the Tim Van Laere Gallery, in Antwerp, last winter. Inspired by Les Très Riches Heures, an illuminated book of hours created in the 15th century for the duc de Berry and featuring in some of its illustrations a castle wall, Ghenie’s The Blue Rain, 2009, depicts a concrete wall receding under a cobalt sky, in front of which are sunbathers, an apparition of Elvis, and an alert German Shepherd. It is an obscure image hinting at the rise of popular Western culture in an impoverished postwar East Germany rapidly coming to terms with its communist present and perhaps taking a step back toward its feudal past. “There are elements of a story, a story with a ’50s or ’60s smell,” the artist says. “But there is no story per se.”

The shadow of World War II and the cold war lies of over many of Ghenie’s paintings, including those in his two key solo exhibitions of 2007: “They said this place does not exist,” at Wohnmaschine, in Berlin; and “The Shadow of a Daydream,” at Haunch of Venison in Zurich. Although the places in the pictures displayed could be anywhere, it is hard not to read them as referring to Ghenie’s homeland.

In his work, the artist has attempted to come to terms with the Romanian dictator Ion Antonescus persecution of Jews and Roma during World War II, his country’s Soviet occupation, and its severe economic difficulties under Ceauçescu, subjects that often appear as oblique or latent subtexts. The Ceauçescu works exhibited in L.A. this spring mark a watershed in this process, bringing contemporary Romania into focus amid the swirl of postwar Europe’s political, social, and economic turbulence.

Adrian Ghenie

January 23 – March 26, 2010 NICODIM gallery

PRESS RELEASE

Mihai Nicodim Gallery is pleased to present the second solo show of Adrian Ghenie in the gallery. Adrian Ghenie, born in 1977, draws his inspiration from personal memories of growing up in communist Romania under the dictatorship of Ceausescu. He witnessed history being written and rewritten, first hand, and that period of transition left a deep impact on him. The artist takes the viewer on a journey through some of the darkest states of human existence - oppression, abjection, tragedy, persecution, poverty, loneliness and misery, hoping to find himself in the grey area between a movie script and real life. In a society thrown in fast forward, Ghenie feels like he is passing through a series of rooms loaded with history and subconscious dark private fears. The mantle of history surrounds Ghenie’s work as well as the artist himself, his paintings are like mental snapshots of crime scenes taken by an uninvolved observer, a material portrayal of the human condition in which the baggage of history weighs heavily on the shoulders of the present.

In this new body of work, Ghenie offers a contemporary position on a universal theme of those abusing power and those abused by them. It’s not just the execution of his paintings that reminds us of the heavy substance of the mantle of history, but also their content, which is narrative filled with historical facts, though not explicitly telling a clearly defined story. That’s the case for the „Berlin Zoo“ series which carry the metaphor of the traumatic collective experience of the Iron Curtain. The Iron Curtain was the way Europe was viewed after World War II. Physically, it took shape in the Berlin Wall.

Berlin Wall served as a longtime symbol of the ideological, military, economic and physical boundary between Eastern and Western Europe. The ideological divison put to the East all the countries connected to or influenced by the former Soviet Union, ruled by communist dictators and which struggled for freedom until the fall of the Berlin wall.

The collective struggle in communist Romania ended up in 1989 with the brutal execution of Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu, the abusive dictator and his wife, by a secret military tribunal which found them both guilty of genocide and crimes against the state. In „The Trial“, Ghenie’s powerful painterly language navigates from the grotesque to the sublime in depicting the last minutes before the execution of the dictators by a firing squad, ending the dictator’s 24 years as communist party leader and Romania’s president - during which he suppressed all opposition using brutal force.

The trial lasted for just under an hour. Watching the proceedings, one is filled with a queasy sense of history at its rawest, stripped to brutal fundamentals. Here are two living people, once powerful rulers of their country, now defenseless, about to become dead. How would it have been, one wonders, to see the show trials of King Louis XVI of France or Marie Antoinette or the trumped-up trial of Anne Boleyn? This comes pretty close. Once the sentence was pronounced, four soldiers approached the couple to tie their hands with a crude ball of twine. The intention was apparently to shoot them one at a time but they insisted on dying together. The footage of the trial takes on an unrefined, unedited quality far more dramatic than any Hollywood production.

Adrian Ghenie recently showed in the Liverpool Biennial (2009), Prague Biennale (2009, 2007) and had solo shows at Haunch of Venison Zurich and London, Tim Van Laere, Antwerp, NolanJudin, Berlin and Galeria Plan B, Cluj and Berlin. He is currently having a solo show at the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Bucharest and his upcoming solo at S.M.A.K., Ghent opens December 2010. His work is in the permanent collections of Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, MOCA, Los Angeles, S.M.A.K. , Ghent and Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst, Antwerp.

Interview

Adrian Ghenie

Rise & fall

by Magda Radu

Duchamp’s Funeral (detail) (2009). Courtesy Nolan Judin, Berlin.

Prior to becoming the “Transylvanian rising star,” Adrian Ghenie co-founded, together with Mihai Pop, Plan B gallery, the epicenter of the vivacious art scene in Cluj, Romania. He is committed to supporting the thriving artistic environment in this small Romanian town through his involvement in a new art space — a reconverted industrial hall housing several galleries and studios — that opened this fall.

Magda Radu: You deliberately leave room for the intervention of hazard and for arbitrary choices when you paint. To what extent does this interfere with the control you have over the painting process?

Adrian Ghenie: When I provoke an accident and I let the oil or acrylic paint leak over a surface, I get interesting results and satisfying solutions that I haven’t thought about. Representational painting can be quite tedious when it comes to the painterly facture, when paint is applied with a brush in a conventional way. The mix of colors resulting from accidents endows the compositional elements with vibrancy and I use this type of execution when I paint the background. In my works, the space framing the figures has to be painted as loosely as possible.

MR: There is a tension in your work between a carefully planned preparatory stage (the making of collages and models) and the actual process of translating that into painting. Can you comment on this?

AG: An antagonism is embedded in my paintings, which is not something I was fully aware of. On one hand, I work on an image in an almost classical vein: composition, figuration, use of light. On the other hand, I do not refrain from resorting to all kinds of idioms, such as the surrealist principle of association or the abstract experiments which foreground texture and surface. If the distribution of elements is precisely premeditated, paint is nonetheless applied freely, with unbridled gestures. The oil paint medium triggers a range of technical possibilities, which I am committed to explore in various combinations. For example, I mix various colors on a trowel and I apply it directly onto the canvas. Then I wipe it off with something else. Quite often I paint with a house-painter’s brush. I’m interested to see the outcome of such exercises.

MR: You have started making large-format paintings and recently your palette has diversified. What brought about these changes in your practice?

AG: I wanted to confront this diversity, to test the combinatory possibilities after a period in which I employed an almost monochrome tonal range that reduced the intensity of experimentation. The decision to adopt a larger format came out of the same curiosity. Looking at Renaissance painting, I was keen to explore pictorial issues regarding the construction of space, such as the succession of planes, the use of perspective. My inclination to investigate geometry and volume demanded — for me at least — a bigger dimension to work on. At the same time, I was drawn to the illusionistic power of the cinema screen.

The Collector (detail) (2008). Courtesy Plan B, Cluj/Berlin.

MR: Can you describe the impact of film on you and your work?

AG: If you look at my works, there is a filmic quality in all of them. In my case, the film has provided the most important ingredient of my visual background. When I paint I have the impression that I am also involved in directing a film. Looking at a film made by Lynch or Hitchcock, experiencing the tension and drama of a thriller is at once realistic and beyond the ordinary. For me, the genius of cinema resides in its capacity to project an illusion. The emergence of every artistic medium relied on a technical invention that was originally designed to serve a practical purpose. At the beginning there was no aesthetic. All of a sudden one looked at moving images that previously existed only in one’s imagination. The first films had a certain type of grandeur because they captured historic moments, stories and myths that had to be represented on screen. There was the need to create worlds, inaccessible in everyday life. In the same vein, when the van Eyck brothers invented the oil painting technique they realized that it had the capacity to render details, texture, volume with an astonishing accuracy. An accidental slip of the paintbrush could yield unexpected results, looking like sand or fur or the leaves of a tree. Once you discover the potential of such an invention you cannot resist it. To the 15th-century spectator, the combination of religious subject matter with the illusionistic power of oil painting must have had a great emotional impact. The same effect was experienced by the viewer in the early days of cinema.

MR: How do your works convey this cinematic feeling?

AG: The cinematic impression is partly given by light and texture. The settings in my paintings seem real; they seem to have suffered a process of erosion, you recognize in them a diversity of textures. The background, enclosing human silhouettes, is made up of wet, burnt, damaged walls.

MR: What about the historical avant-garde and the way it is insinuated as a subject in your paintings? You conjure up the Dada Berlin exhibition or Duchamp.

AG: The state of painting today prompted me to choose this subject. The ongoing debate about the “death of painting” may be intellectually stimulating, but I think it is also anachronistic. There is enough evidence to conclude that painting is not dead. And yet, I wanted to return to the historic context in which this problem was first articulated. I view key moments and personalities of the avant-gardes like Duchamp from a great distance and from a reversed perspective. Although I recognize the liberating effects produced by the outburst of the avant-garde movements (of which I am also a beneficiary), I can’t help but notice the extent to which some of their ideas — exposed in time to manifold appropriations — have imposed themselves with such forcefulness as to become canonical. I simply want to question this state of affairs without making accusations. But I feel I have the right to see idols like Duchamp or Dada in a different light.

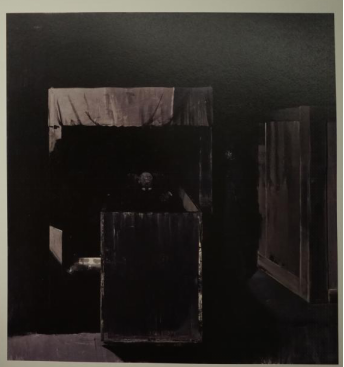

Dada is Dead (2009). Courtesy Haunch of Venison, London.

MR: There are also references to the history of the 20th century, to figures like Lenin, Hitler or Goering. Do you invoke them because you want to address contemporary issues?

AG: We inevitably live in a post-WWII epoch, which means that we constantly have to look back to that watershed moment in order to understand our present condition. Rather than historic figures, Hitler and Lenin appear as ghosts in my paintings. Indeed, I chose to paint them in very few instances and their presence is not conspicuous at all. It was a period in which I tried to depict their residual image in the collective unconscious, painting after such clichéd photographs like the ones with Lenin lying dead, an image familiar to millions of people. With Goering — whose portrait was featured in “The Collector” series — the motivation was slightly different. I was more interested in his personality; for me, he truly embodied the archetype of the rapacious collector. I tried to grasp the psychological complexity of this man driven by a collecting bulimia, which in the end was totally compromised by his power.

MR: Your work is often discussed in relation to Communism. Last year you appeared in a video-film painting a portrait of Ceaușescu. To what extent does your work deal with the legacy of Communism?

AG: I am particularly interested in the state of exceptionality that characterizes everyday life in totalitarian regimes,(极权主义政权中的日常生活的特殊状态) not just Communism. In such circumstances everything is being distorted. However, in terms of subject matter, national-socialism民族社会主义 is more present in my work. But there are more subliminal潜意识的, subterraneous ways in which I was marked, for example, by early memories of my life lived under the Communist regime. The basement of our family home was a space which contained many objects that were discarded, and this space represented for me the true receptacle of personal memories个人记忆的真实容器. The painting Basement Feeling (2007) is one of the few autobiographic works that captures this melancholic encounter with my past. The work with Ceaușescu is a project by Ciprian Mureșan; he wanted me to paint an official portrait of the dictator, giving me indications to comply to all the parameters of a conventional and neutral posture, as if an artist of that epoch had received this commission. The overwhelming majority of such portraits were horribly painted and ridiculous, so we wanted to find out if, given the imposed iconography, it was still possible to make an aesthetically passable work. It is an open experiment; the portrait turned out ok, but still, we didn’t exactly live in those times.

Basement Feeling (2007) 35cmx44cm

The Dark Side of Art

“It became clear to me that people’s perspective of history is always, quite naturally, a distant one. And that is precisely what is disgusting.” (Adrian Ghenie)我清楚地认识到,人们对历史的看法总是自然地是遥远的。这正是令人厌恶的

Hitler and his lover Eva Braun, dead in the Führer’s bunker. A deceased Lenin lying in state. A man frozen in the middle of the act of wiping buttercream frosted cake crumbs from his face—along with what seems to be his skin. These are mysterious, disturbing pictures, exerting a pull that one can barely escape.

So it is no wonder that Adrian Ghenie made the leap to the top ranks of the international art world in just a few years. After finishing his studies in 2001, the Romanian artist was exhibiting his work in solo shows in Romania, Switzerland, the United States, Germany, Belgium, and Great Britain by 2006. In 2009 the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Bucharest devoted a first retrospective to him. Subsequently, his work was acquired by the collections of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, among others.

Ghenie, who grew up in Romania during the years of the Communist dictatorship under Nicolae Ceausescu, is a teller of histories. He sends his viewers on a journey through time, giving them a look at his interpretation of 20th-century history in a grand narrative style. Power and its abuse in totalitarian political systems is one of his central themes. For instance, in the painting Dada is Dead (2009), based on a photograph of the First International Dada Fair in Berlin in 1920, Ghenie recalls Hitler’s headquarters in East Prussia, also known as Wolfsschanze, and thus revives awareness of the fates of the “degenerate,” ostracized artist.

The artist is especially interested in the gap between grand, “objective” history and subjective memory. In an interview he pointed out the contradictory experience of history, using his mother, who spent her youth in Communist Romania, as an example. “She lived through the worst period of the 20th century; when I asked her about it, she only said that it had been a great time … It became clear to me that people’s perspective of history is always, quite naturally, a distanced one. And that is exactly what’s disgusting. She is not interested in the fact that these were the Stalin years.”(他画这些历史题材的原因,可能是想人们想起和关心,由历史中学到教训。)

Ghenie bases his compositions on historical photos, bits and pieces from films and the Internet, things borrowed from huge vault of art history, and personal memories, which he sometimes turns into collages or three-dimensional models.

For example, a photograph of inhabitants of the Warsaw Ghetto was used for Nickelodeon (2008); a photograph of Hermann Göring from the Nuremburg trials was the basis for the portrait of the Third Reich minister in The Collector I (2008); he also makes use of countless other historicalphotos from Nazi propaganda postcards, which Ghenie often finds in the German History Museum in Berlin. On the other hand, photographs of the US military formed the basis for an early group of works titled Unbound (2006/07), subtle black-and-white paintings of atomic weapons tests in a contemporary kind of grisaille on canvas.

In his Pie Fight Studies, the artist took scenes from short American slapstick films featuring artists such as The Three Stooges or Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, in which the protagonists often serve up pie fights. Ghenie most frequently employs the Internet as his source, however. “When I started using these film stills, it became clear to me that they are psychologically profound, very powerful images. They’re about humiliation, a very strange human ritual, and still one of the most important characteristics of a dictatorship.” A comedic motif—the pie fight—becomes a brutal gesture.

For Boogeyman (2010) the artist refers to his own life. According to Ghenie, the details are taken from a 1980 furniture catalogue that his mother ordered from Germany.

For his somber scenes, Ghenie mainly limits his palette to black, gray, and dark red; only recently has he started to lighten it more and more. The paintings have a great tactile and material allure: often the artist applies several layers of paint to the canvas and then scrapes some of them off later. He works with a brush, as well as with a steel putty knife, combining his individual signature with a mechanical gesture. Painting is made visible as such. Again and again the paintings bring to mind the great masters of the Baroque period and their dramatic chiaroscuro.

Figures and interiors oscillate between the figurative and the abstract, appearing realistic and indeterminate at the same time. “Portraits” of Adolf Hitler, Josef Mengele, Stalin, Lenin, and Nicolae Ceausescu, for instance, are recognizable at first glance, but the faces are often rudimentary or vague, as if they have been concocted by a witness who does not want to remember too many details. Their terrible histories evoke all kinds of uncanny, repressed, unruly things: the ghosts that lurk within everyone. Thus, as viewers, we have the feeling that from out of these pictures of the dark moments of 20th century history the gaze of the present emerges to meet ours.

November 4, 2013, Stefanie Gommel

Interview magazine

ART

ADRIAN GHENIE

By ALEX GARTENFELD

Photography SEBASTIAN KIM

Published 01/05/12

Ever since the Wall fell in 1989, Berlin has been the city that artists have defected to—in part for the cheap living and studio space, in part to get away from the hungry market and social swirl, and in part for all of the dirty, glamorous decadence that has made the fraught German capitol a place of myth and mayhem for generations of young misfits. Artists don’t come to Berlin to make it big—they come to be artists, and today, a new crop of international creators have arrived to make the city their own.

With figures gnawed and slashed, blurred and speckled, Adrian Ghenie’s paintings involve the big ideas that transform men into larger-than-life emblems. Ghenie’s recent exhibition at Haunch of Venison in London featured humans wildly distorted and many with monkey features. The canvases were inspired by the Nazi’s ideological bastardization of Charles Darwin’s theories of natural selection. “No discovery is ever good or bad—it depends on how you use it,” says Ghenie, although his portraits frequently feel cautionary and almost malicious in their gestural violence. Take for example his depictions of notorious Holocaust doctor and torturer Dr. Josef Mengele, his features scraped away or washed out. Other faces are patchworks of textures, so skin appears as if sourced from different ages. It’s pretty brutal stuff. “Reading the biography of Mengele, you realize the Nazis were normal, obscure bureaucrats—then something happens that corrupts them,” says Ghenie. “It could happen to you or me or anyone.” Indeed, the show included a silhouette of the artist himself, wearing a mask of Darwin’s features. It’s an approach that’s no doubt additionally charged for an artist who is based in Berlin. The 34-year-old moved part-time to the city in 2007 from Cluj, Romania. Growing up in a small industrial town, Ghenie compared official painters from his native country with the classics of the Western canon, while his personal brushes with art come largely from the experiences of his parents. Ironically, the time of communist insularity of the ’50s and ’60s proved to be the era of greatest freedom for his parents, who traveled across Eastern Europe in the ’60s and ’70s and imparted those memories to their son. Ghenie sees a connection with those family tales and his own artistic production: “I like the difference between the official story and the personal perspective.”

Art21 magazine

Letter from London: Dead as a Dada

by Ben Street | Jun 30, 2009

ghenie_hv25573

Adrian Ghenie, “Duchamp” (2009)

The problem with writing about contemporary painting is that it ends up being an excuse for a riffle through the thesaurus for the most headily baroque terms to describe the look of paint on canvas. This isn’t a problem when writers write about old paintings, because they tend not to focus on the physical presence of the work, instead treating a painting as a sort of rebus to be decoded and tacked on to a pre-existing idea. Renaissance art historians tend to look through, not at, the paintings in question. Contemporary painting has a hard time because decoding content isn’t what you’re supposed to do; you’re supposed to focus only on the physicality of the thing in front of you: at, not through. The language of at is evasive and slippery and is simply beyond the limits of the technical vocabulary of orthodox contemporary artspeak, like a caveman trying to describe the Internet. Hence the preponderance of purple prose in exhibition catalogues and press releases, laden down with nightmarish adjectival pile-ups more akin to lip-smacking restaurant reviews than anything to do with art.

Adrian Ghenie’s current show at Haunch of Venison on London presents the writer on contemporary painting with what looks like an easy premise: recognizable representational content. His suite of oil paintings collectively titled (like a Cure B-side), Darkness for an Hour, at first look visually pleasing in a loose-and-tight kind of way—neither too finicky and faux-outsiderish, nor too slappy and faux-hamfisted to put off a contemporary art cynic. Ghenie lays on the paint with just the right amount of visual splashiness to look modern and self-aware, while retaining a finessed draftsmanship in the rendering of figures which looks like an appeal to old-timey painterly virtues. To come away from the show feeling as though you’d just wandered through a needy MFA graduate resume (look! I can do abstract painting! Wait: do you like pictures of people? How about BOTH?), which I nearly did, would be understandable but unfair, because of something very rarely discussed or even considered worthy of discussion in contemporary artspeak: content.

Ghenie’s quotations of earlier paintings are there—photo-sourced multi-figure compositions recall both Michael Andrews and Larry Rivers, with areas of squeegeed abstraction out of Richter—but I suspect the references are lightly held, a resonant means of conveyance rather than allusive game playing. These are communicative, gregarious paintings that are emphatically narrative, not obliquely referential. If the heart sinks a bit at his employment of modernist art icons as protagonists (given the contemporary orthodoxy of sneering at modernism), his teasing out of mordant narratives replays well-trodden art historical episodes with a melancholy wit that’s both accessible and alien.

In his painting Duchamp (2009), everyone’s favorite conceptual art behemoth sits swamped in his fur coat, hat in hand against what looks like a railing as a broiling sea churns beyond. While the source image must have been a photograph, it’s not part of the standard repertoire of Duchampian portraiture. The wry smile and supercilious air have been replaced by a creased brow and pensive hand on the chin. His instantly recognizable face is lost in a wash of smears, like a photograph seen through running water, and Ghenie stages a battle of there and not-there, description faltering at the verge of readability. This is the artist in exile, carried across the Atlantic to lasting adoration yet strangely lost, anxious, and almost literally disembodied. In another painting, Urinal, Duchamp’s 1917 Fountain (the urinal on a pedestal) is inspected by a frock-coated officer in a gas mask in a low-lit storeroom. The title’s performance of a reverse magic spell on the found object tradition gives voice to the conceptual art elephant in the room: a urinal? As art? Why did we ever think that? It looks weird and sad, like something out of a time capsule you buried in the past and now can’t remember why.

Adrian Ghenie, “Duchamp’s Funeral II” (2009)

Dada appears again as a reference point in Ghenie’s Dada is Dead, which restages the famous photograph of the 1920 International Dada Exhibition, with John Heartfield’s Prussian Archangel (a pig-faced soldier mannequin) bumping along the ceiling and (anachronistically) a Malevich black cross hanging on the wall, each a component of a secular iconography dependent upon the ghosts of art past. Angels and crosses allude to a secularized transfiguration absolutely at the core of Dadaist found object principles, but in Ghenie’s muscular assertion of the primacy of paint, how archaic that religion looks now. A slash of light illuminates a wolf stalking the abandoned gallery, frozen mid-prowl, come to pick the bones clean. The painting has a lovely reflexive weirdness. How strange that Dada is dead, how strange it ever lived, and how strange and surprising that it should be painting that performs the eulogy.

Death and demise overshadow Ghenie’s work. Two paintings depict Duchamp lying in vampiric state: one surrounded by Diana-style cascades of wreaths and bouquets in an otherwise empty space, the other in a modernist apartment complete with Mies chair and movie camera. The paint is applied ecstatically, drooling down the canvas and jumping about in big Ab Ex swathes in somber dark reds and pale grays. On the one hand, it’s an assertion of the undead art of painting itself, perpetually self-vivifying and vital; on the other, its allusiveness is a token of historical distance, of the lost world of the past. Ghenie’s paintings, like Hollywood zombies, are full of an animation that emphasizes death, images jerked alive by jolts of paint, but strange and unsettling and absent nonetheless.

Darkness for an hour

Haunch of Venison

Haunch of Venison, London

15 May - 25 July 2009

Haunch of Venison brings Romanian painter Adrian Ghenie’s first solo exhibition in Britain, until the 25th July 2009. Situated in the mass expanse of the Western Gallery, Ghenie’s work adds another successful exhibition to the Haunch of Venison’s repertoire, solidifying its reputation as a house of leading contemporary artists, which primarily focuses on post war and European artists.

Darkness for an Hour brings together a collection of work by Ghenie that succeeds in portraying his continuing fascination and interest in the exploration of painting, enthralment with European history as well as Dada, with a recurrent theme running throughout this exhibition of Duchamp. The narrative fixtures of each painting, which also represent Ghenie’s interest in cinematic langue and aesthetic seen in his previous works ‘Flight into Egypt’ (2008), Dig and Hide (2007) and ‘They say this place does not exist’ (2007), where the figures appear to be pre occupied with the narrative fixture, each homed into the space Ghenie provided them, provides the viewer with a visual and aesthetic feast. His dark portrayals with a limited colour palate of dark and sombre hues, drips of paint sprawling themselves through each canvas, captures an echo of remembrance. The presence of Duchamp in numerous paintings adds a new and ongoing theme in Ghenie’s work, which explores Dada and displacement, furthering the connection with his previous work. Duchamp in Darkness for an hour is seen in a coffin, his funeral and as a blind man and the death of Dada renders the painter as a hopeless figure.

His paintings are put together though an excavation of mass media, correlating a shared history with his viewers who consume the same mass stories. Yet his paintings are neither nostalgic nor sickeningly emblematic. Each painting is open to a myriad of interpretations; of a past that haunts the presence, of remembrance so one does not forget. They do not hold upon a singular meaning that imposes itself on the viewer, rather, they impart and depict an interest, which situates these paintings into a milieu of aesthetically appealing and singular paintings that cultivate in an exhibition that launches Ghenie’s work in Britain.The exhibition pulls together his repertoire of interests and does not fall short of fulfilling each one of them.

And it is for this reason that the paintings do not get lost in the mass of space available in the Western Gallery, broken up by walls and entrances for the viewer to walk through and find another piece of Ghenie’s work. The space gives Ghenie’s work the respect they deserve, inviting the viewer to walk around, spend time with each painting in a continuous view of each one. Even the smaller portraits are given their own space to sing. These smaller pieces on an expanse of white wall bring you closer in so that you are at a level where you can see the painstaking etching and paint drips across the canvas, immersing the viewers and sinking them due to his dexterity and subversion of perspective. Each emotion that Ghenie experiences while each painting is evident through each brush stroke and technique. His gloriously dark technique excavates his interest in Dada.

The similarities between Ghenie and Francis Bacon are ever present with Ghenie’s techniques creating a haunting yet deeply absorbing place. His comic figures of Laurel and Hardy create an oeuvre of comedy, yet unsettling through the perspective and displacement of the figures, creating a world that is visually distressing, yet the technical skill of Ghenie ensures that the viewer is pulled further in rather then walking forth out of horror or distaste.

Roul Hausmann, (born July 12, 1886, Vienna, Austria—died February 1, 1971, Limoges, France), Austrian artist, a founder and central figure of the Dada movement in Berlin, who was known especially for his satirical photomontages and his provocative writing on art.

Hausmann was first exposed to art through his father, the painter and professional conservator Victor Hausmann. The family moved to Berlin in 1900, and in 1908 Hausmann began his formal training at Arthur Lewin-Funcke’s Atelier for Painting and Sculpture, where he focused on anatomy and nude drawing. Upon finishing at the atelier, Hausmann connected with the German Expressionist painters—in particular, Ludwig Meidner and Erich Heckel. He studied lithography and woodcutting under Heckel. He also began what would become a lifelong writing career, penning articles that decried the art establishment for journals such as Die Aktion and Herwarth Walden’s Der Sturm.

In 1915 Hausmann met artist Hannah Höch, with whom he began an extramarital affair (Hausmann married his first wife in 1908 ) and an artistic partnership that lasted until 1922. Hausmann was engaged in and loyal to Expressionism until 1917, when he met Richard Hülsenbeck, who introduced him to the principles and philosophy of Dada, a new visual and literary art movement that had already taken off in other cities in Europe. Dada artists and writers created provocative works that questioned capitalism and conformity, which they believed to be the fundamental motivations for the war that had just ended and left chaos and destruction in its wake. Along with Hülsenbeck, George Grosz, John Heartfield, Johannes Baader, and Wieland Herzfelde, Hausmann founded the Berlin Dada Club and, with Hülsenbeck, wrote a manifesto claiming that Dada was the first art movement that “no longer confront[ed] life aesthetically.” Hausmann also wrote a manifesto titled “The New Material in Painting,” in which he demanded an alternative to traditional oil paint. He later published the piece as Synthetisches Cino der Malerei (“Synthetic Cinema of Painting”). Both the anti-art Dada manifesto and Hausmann’s declaration on new media were recited before a riotous audience at the first event of the Berlin Dada Club, on April 12, 1918. The artists’ evening of performance and readings was staged at a meeting of the Berlin Sezession, a breakaway group of artists, including Lovis Corinth and Max Liebermann, still very much devoted to traditional art forms.

By 1918 Hausmann had already begun to work primarily in photomontage—composite collaged images made by juxtaposing and superimposing fragments of photos and text found in mass-media sources. It is commonly held that Hausmann and Höch discovered photomontage while vacationing on the Baltic Sea in the summer of 1918. Notable photomontages by Hausmann include Art Critic (1919–20), a satirical image of a man in a suit with a German banknote behind his neck, choking him , and A Bourgeois Precision Brain Incites a World Movement (later known as Dada Triumphs; 1920), a montage and watercolour that conveys with text and image the global takeover of Dada.

Between 1918 and 1920 Hausmann was also busy inventing other anti-art art forms, such as “optophonetic” and “poster” poems, both of which were made up of random letters strung together. The former were meant to be performed or read aloud; the latter were visual poems created as collages of typography. Two of his best-known works of this type are the poster poem OFFEAHBDC and the optophonetic poem OFFEAH (both 1918). Hausmann also created, as an offshoot of the collage and photomontage, assemblages of found materials, including arguably his most famous work, Mechanical Head: Spirit of Our Age (1919–20), a hairdresser’s wig dummy adorned with a tape measure, a wooden ruler, a tin cup, a spectacles case, a piece of metal, parts of a pocket watch, and pieces of a camera.

Along with Heartfield and Grosz, Hausmann in 1920 helped organize the First International Dada Fair, a subverted version of an academic art exhibition. Works of art—defined as such by the Dadaists—were crammed into a small gallery, and all were for sale. Among the works Hausmann exhibited at the fair are some of his best known: a photomontage (now lost) bearing the title of his 1918 manifesto, Synthetisches Cino der Malerei; a collage-photomontage titled Self-Portrait of the Dadasoph; an ink drawing, The Iron Hindenburg; and a photomontage including the face of Russian artist Vladimir Tatlin, Tatlin Lives at Home (all from 1920). All of the aforementioned works include some visualization of a mechanized human, a man-machine hybrid. On the cover of the exhibition catalog was Hausmann’s photomontage and collage Elasticum (1920), which includes images of tires, a speedometer, nuts and bolts, and, most likely, the head of Henry Ford—inventor of the assembly line and father of mass-produced automobiles. Throughout the Dada era, which flourished for about six years (1916–22), Hausmann contributed his “Dadasophy” (his philosophy on Dada) to several publications and edited the journal Der Dada (which produced only three issues, 1918–20). In 1923 Hausmann created his final photomontage, titled ABCD: his face appears at the centre of the image with the letters ABCD clenched in his teeth, and an announcement for one of his poetry performances is collaged right below his chin.

Somewhat surprisingly, after that final Dada photomontage, Hausmann turned to more-traditional media: photography and drawing. His photographs consist primarily of nudes, landscapes, and portraits. He also continued to write and publish regularly, sometimes in relation to his theories about the uses and possibilities of photography. Under the scrutiny of the Nazi Party, he and his second wife, artist Hedwig Mankiewitz, who was Jewish and whom he had married in 1923, and their lover, Vera Broido (also Jewish), left Germany for Ibiza, Spain, in 1933. While in Spain Hausmann wrote about and photographed the country’s indigenous architecture and published his work in several French-language journals, including Oeuvres and Revue anthropologique. During that period, as a result of his ongoing research and interest in the relationship between the audible and the visual, he invented the “optophone,” a mechanism by which to convert visible forms into sound, for which he got a patent in 1935. At the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, Hausmann and Mankiewitz left Spain, first stopping in Zürich and then going to Prague and Paris. Between the onset of World War II (1939) and the Allied invasion of France (1944), they lived in hiding in Peyrat-le-Château, France. They settled in Limoges in late 1944.

In the late 1940s and the 1950s, Hausmann continued to pursue photography, exhibited often, and published articles on photography in journals such as A bis Z and Camera. He also published writings on his recollections of Dada, including an autobiographical volume called Courier Dada (1958). During that period and through the last two decades of his life, in addition to engaging in photography, he created photograms, recorded sound poetry, and returned to oil painting. His final piece of writing, Am Anfang war Dada (“At the Beginning Was Dada”), was published posthumously in 1972.

Drowne,K and Huber,P. (2004) The 1920’s. London:Greenwood Press.

By the end of the 1920s, several important art museums had begun to include photographs in their displays, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art, and the careers of such famous art photographers as Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, Edward Steichen, Edward Weston, and Man Ray had been launched.

Art photography, however, constituted only a tiny aspect of the world of photography during the 1920s. Amateur photography was far more widespread and, indeed, was an exceptionally popular pastime during the decade.(P.284)

No comments:

Post a Comment